AK

Size: a a a

2021 August 12

тонны метеостанций на ардуинах по 2000 рэ за штучку?

A

а не-впк невыгодно

I

Сейчас все стоящие изделия превращаются в стартапы.

SR

How to get channel_id of data?

S

Советская и российская электроника всегда отставала и будет отставать. Виноваты в этом прежде всего головы в этой сфере. Иное виденье мира у них.

p

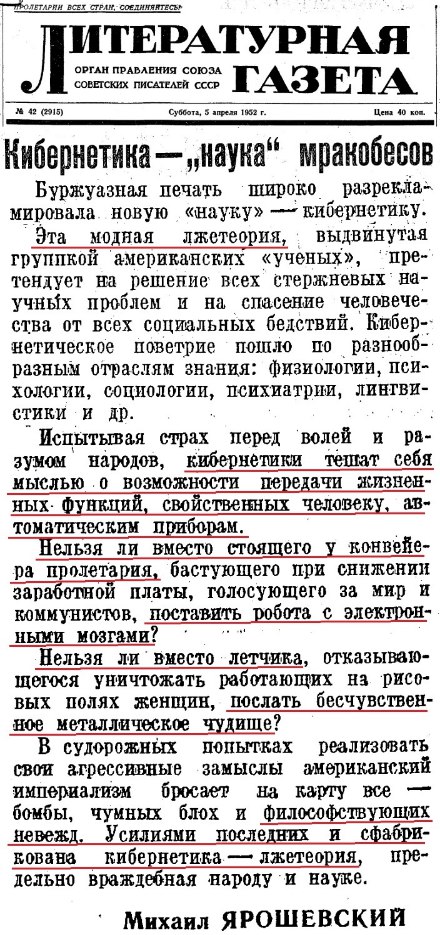

Здесь корни проблемы, как мне кажется, в мнении определённой кучки философов, на заре компьютерной эры форсившей кибернетику как лженауку (пока за этих самых философов всерьёз не взялся Ляпунов).

KS

https://www.mccme.ru/edu/viarn/2008/Echo-25-26.htm

"С другой стороны, наш замечательный математик и механик М.В. Келдыш ценил российскую математику настолько высоко, что даже считал ненужным разработку в СССР новых компьютерных систем: он считал, что наши математики и без компьютеров сумеют создать и ракеты, и бомбы, которые потребовали у американцев новой компьютерной техники."

"С другой стороны, наш замечательный математик и механик М.В. Келдыш ценил российскую математику настолько высоко, что даже считал ненужным разработку в СССР новых компьютерных систем: он считал, что наши математики и без компьютеров сумеют создать и ракеты, и бомбы, которые потребовали у американцев новой компьютерной техники."

p

Если быть честным, мне кажется, что в глубине души Арнольд - лютейший тролль, любящий разбавить объективную реальность дополнительным вписыванием взаимоисключающих параграфов, создавая тем самым дополнительные точки бифуркации.

KS

Источников не много, кроме Арнольда. Но я видел ссылки на журнал кибернетика только на заре CS

KS

Переслано от Kepler’s Supernova

KS

Ну и если уж совсем далеко копать, то вычислительная техника началась с телеграфа и табуляторов, оба в США)

В первом случае вообще удивительно как художнику дали инвестиции на связь) во втором все было прагматичнее - надо было посчитать налогоплательщиков быстрее чем пребывало их количество

В первом случае вообще удивительно как художнику дали инвестиции на связь) во втором все было прагматичнее - надо было посчитать налогоплательщиков быстрее чем пребывало их количество

KS

In the year 1811, Benjamin West, the President of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, and then past seventy years of age, was enjoying the noontide splendor of his fame as the great historical painter of England. During his presidency the Academy had a high reputation, for he was an eminent instructor, and young men from many lands went to it to learn wisdom in Art.

On a bright autumnal morning in the just mentioned, West's beloved American friend, Washington Allston, entered the reception-room of the venerable painter, and presented to him a slender, handsome young man, whose honest expression of countenance, rich brown hair, dark magnetic eyes and courtesy of manner, made a most favorable impression upon the president. This young man was Samuel Finley Breese Morse. He was then little more than nineteen years of age, and a recent graduate of Yale College. He was the eldest son of Rev. Jedediah Morse, an eminent New England divine and geographer. Rev. Samuel Finley, D.D., the second president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, was his maternal great-grandfather, from whom he inherited the first portion of his name. Breese was the maiden name of his mother.

At a very early age young Morse showed tokens of taste and genius for art. At fifteen he made his first composition. It was a good picture, in water colors, of a room in his father's house, with the family — his parents, himself and two brothers — around a table. That pleasing picture hangs in his late home in New York, by the side of his last painting. From that period he desired to become a professional artist, and that desire haunted him all through his collegiate life. In February 1811, when he was nearly nineteen years of age, he painted a picture (now in the office of the Mayor of Charlsetown, Mass.) called "The Landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth," which, with a landscape painted at about the same time, decided his father, by the advice of Stuart and Allston, to permit him to visit Europe with the latter artist. He bore to England letters to West, also to Copley, then old and feeble. From both he received the kindest attention and encouragement.

Morse made a carefully-finished drawing from a small cast of the Farnese Hercules, as a test of his fitness for a place as a student in the Royal Academy. With this he went to West, who examined the drawing carefully, and handed it back saying. "Very well, sir, very well; go on and finish it." "It is finished," said the expectant student. "O, no," said the president. "Look here, and here, and here," pointing out many unfinished places which had escaped the undisciplined eye of the young artist. Morse quickly observed the defects, spent a week in further perfecting his drawing, and then took it to West, with confidence that it was above criticism. The president bestowed more praise than before, and with a pleasant smile handed it back to Morse, saying, "Very well indeed, sir; go on and finish it." — "Is it not finished?" inquired the almost discouraged student. "See," said West, "you have not marked that muscle, nor the articulation of the finger-joints." Three days more were spent upon the drawing, when it was taken back to the implacable critic. "Very clever indeed," said West, "very clever; now go on and finish it." — "I cannot finish it," Morse replied, when the old man, patting him on the shoulder, said, "Well, well, I've tried you long enough. Now, sir, you've learned more by this drawing than you would have accomplished in double the time by a dozen half-finished beginnings. It is not numerous drawings, but the character of one, which makes the thorough draughtsman. Finish one pictures, sir, and you are a painter."

Professor Morse and the Telegraph

published in

Scribner's Monthly: An Illustrated Magazine for the People

March 1873

On a bright autumnal morning in the just mentioned, West's beloved American friend, Washington Allston, entered the reception-room of the venerable painter, and presented to him a slender, handsome young man, whose honest expression of countenance, rich brown hair, dark magnetic eyes and courtesy of manner, made a most favorable impression upon the president. This young man was Samuel Finley Breese Morse. He was then little more than nineteen years of age, and a recent graduate of Yale College. He was the eldest son of Rev. Jedediah Morse, an eminent New England divine and geographer. Rev. Samuel Finley, D.D., the second president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, was his maternal great-grandfather, from whom he inherited the first portion of his name. Breese was the maiden name of his mother.

At a very early age young Morse showed tokens of taste and genius for art. At fifteen he made his first composition. It was a good picture, in water colors, of a room in his father's house, with the family — his parents, himself and two brothers — around a table. That pleasing picture hangs in his late home in New York, by the side of his last painting. From that period he desired to become a professional artist, and that desire haunted him all through his collegiate life. In February 1811, when he was nearly nineteen years of age, he painted a picture (now in the office of the Mayor of Charlsetown, Mass.) called "The Landing of the Pilgrims at Plymouth," which, with a landscape painted at about the same time, decided his father, by the advice of Stuart and Allston, to permit him to visit Europe with the latter artist. He bore to England letters to West, also to Copley, then old and feeble. From both he received the kindest attention and encouragement.

Morse made a carefully-finished drawing from a small cast of the Farnese Hercules, as a test of his fitness for a place as a student in the Royal Academy. With this he went to West, who examined the drawing carefully, and handed it back saying. "Very well, sir, very well; go on and finish it." "It is finished," said the expectant student. "O, no," said the president. "Look here, and here, and here," pointing out many unfinished places which had escaped the undisciplined eye of the young artist. Morse quickly observed the defects, spent a week in further perfecting his drawing, and then took it to West, with confidence that it was above criticism. The president bestowed more praise than before, and with a pleasant smile handed it back to Morse, saying, "Very well indeed, sir; go on and finish it." — "Is it not finished?" inquired the almost discouraged student. "See," said West, "you have not marked that muscle, nor the articulation of the finger-joints." Three days more were spent upon the drawing, when it was taken back to the implacable critic. "Very clever indeed," said West, "very clever; now go on and finish it." — "I cannot finish it," Morse replied, when the old man, patting him on the shoulder, said, "Well, well, I've tried you long enough. Now, sir, you've learned more by this drawing than you would have accomplished in double the time by a dozen half-finished beginnings. It is not numerous drawings, but the character of one, which makes the thorough draughtsman. Finish one pictures, sir, and you are a painter."

Professor Morse and the Telegraph

published in

Scribner's Monthly: An Illustrated Magazine for the People

March 1873

p

Ну,там всё было ещё непрерывное и аналоговое. С моей точки зрения, современная вычислительная техника началась непосредственно с дискретизации сигналов, когда на сцену вышли Котельников, Найквист и Шеннон.

KS

Первые компьютеры прилепили к инфраструктуре телеграфов, я про это

Типа телепринтера, перфолент и прочего. Ну и куски от табуляторов там тоже были

Типа телепринтера, перфолент и прочего. Ну и куски от табуляторов там тоже были

p

Именно. Ярошевский яростно топил кибернетику как науку, в навозе. За что потом Ляпунов ласково причислил его к группе людей, которые, "не разобравшись" грубо говоря, несли чушь.

KS

Ура-патриоты 50s style

p

Ахтунг, сейчас будет большой картинка из оригинала интервью Винера о состоянии дел в советской электронике на 1964 год (там, конечно больше слов о глобальном подходе, но его мнение как современника тех событий, считаю ценным.

p

Title:Machines Smarter Than Men? Interview with Dr. Norbert Wiener, Noted ScientistContributor:Wiener, Norbert (Interviewee)Date:24 February 1964, Periodical:U.S. News and World Report